Why Aged Pu-erh Tea Cakes Are So Valuable

Why are aged Pu-erh tea cakes so highly prized—beyond the commonly cited fact that their numbers decline with time?

The answer lies in a process far more complex than simple aging.

The true value of aged Pu-erh tea is formed through a years-long biochemical transformation known as post-fermentation, driven by specific microbial communities. This process is not simple oxidation, as seen in black tea (red tea). Instead, microorganisms continuously break down large molecular compounds in the tea—such as proteins, cellulose, and catechins—while synthesizing new, more stable small-molecule compounds and aromatic substances.

This irreversible biochemical restructuring—unfolding over decades and repeatedly reshaping the tea—is what gives aged Pu-erh its distinctive and irreplaceable character: deep aged aromas (chenxiang), a mellow and rounded mouthfeel, and subtle medicinal notes.

For this reason, every truly well-preserved aged Pu-erh tea represents a singular outcome of time and environment. Within a specific storage context, each tea cake becomes an unrepeatable biological record—where time is the sole director, microorganisms are the protagonists, and the final tea liquor is the artistic expression of this slow biochemical evolution. This is the true origin of the phrase “the older, the better” in Pu-erh tea.

Aging Potential Across Different Forms of Pu-erh Tea

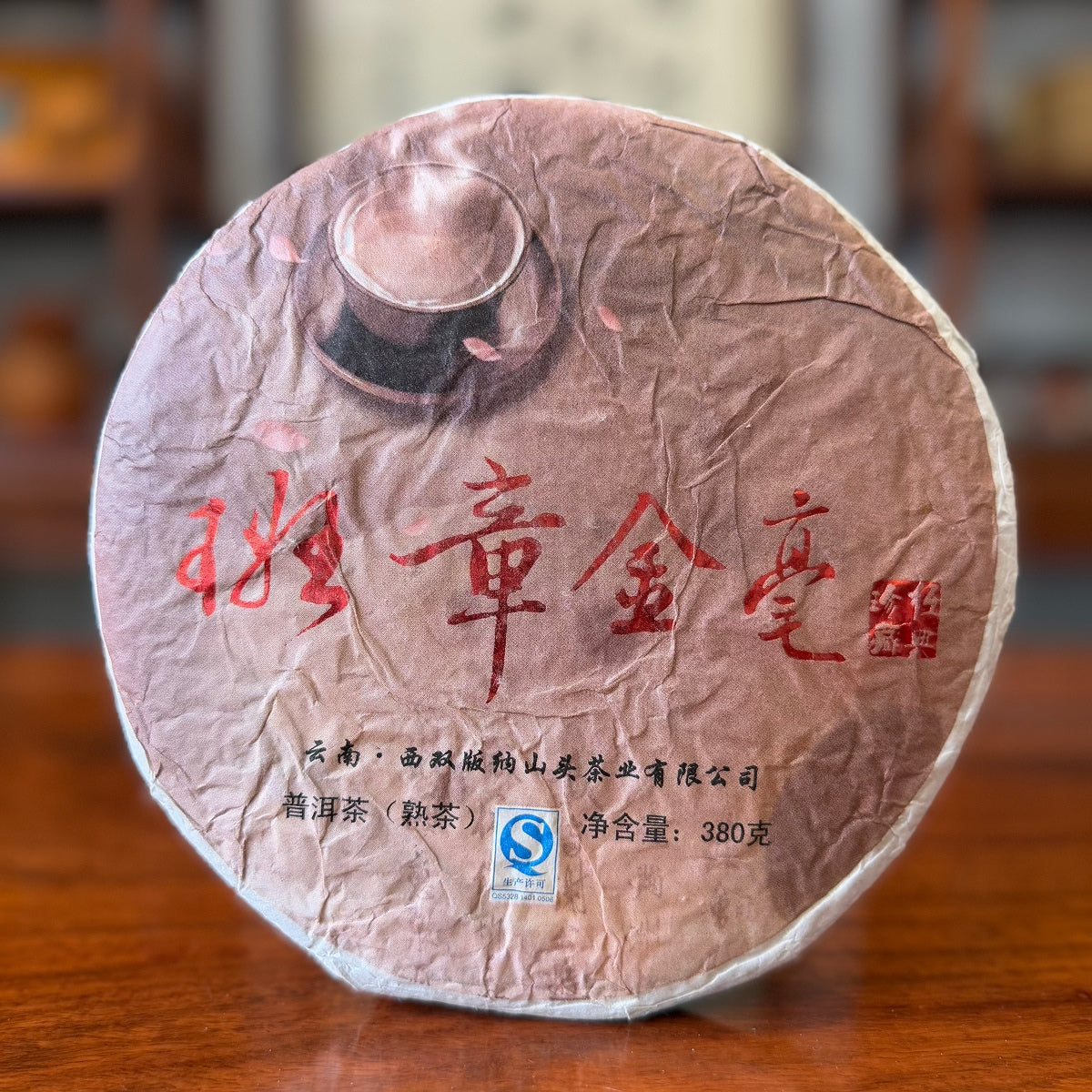

From a professional tasting and collecting perspective, under stable and appropriate storage conditions, all forms of aged Pu-erh tea—whether cakes, bricks, tuocha, or loose leaf—can reach a mature drinking stage and possess varying degrees of collectible value.

Why, then, when discussing long-term value on this collection page, do we place particular emphasis on Pu-erh tea cakes, rather than bricks, tuocha, dragon balls, or loose tea?

The Pu-erh Tea Cake as an Industry Standard

The answer lies not in subjective preference, but in history, practicality, and market structure.

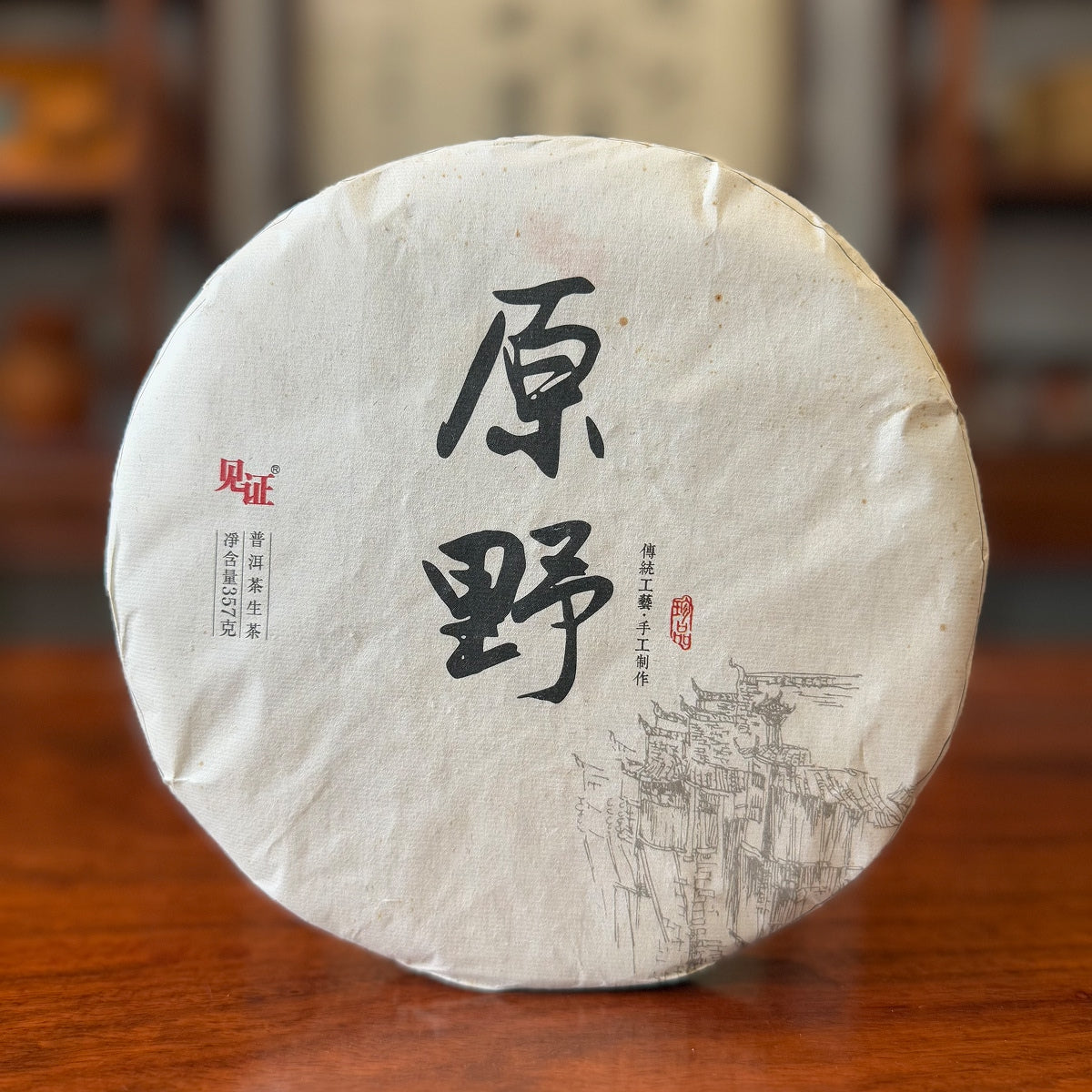

Pu-erh tea cakes—especially the traditional 357g Yunnan Seven Sons Tea Cake (Qizi Bing)—have long been regarded as the industry’s “hard currency.” This status was forged through centuries of use, trade, and consensus, rather than modern marketing.

The name “Yunnan Seven Sons Tea Cake” is not symbolic. Its classic weight originates from the traditional standard of seven cakes per bundle, totaling approximately 2.5 kilograms. Along the ancient Tea Horse Road, this specification met two essential needs: logistical efficiency for caravan transport, and standardized measurement for trade and taxation. Through repeated commercial practice over hundreds of years, this format became deeply entrenched as the most authoritative and widely recognized form of Pu-erh tea.

Structural Advantages for Long-Term Aging

From a physical and structural perspective, Pu-erh tea cakes offer clear advantages for long-term aging when compared with other forms.

Their moderate compression allows for gradual and even internal transformation, while their thickness supports balanced airflow and microbial activity over time. The stable, stackable shape is naturally suited to long-term storage, circulation, and exchange—qualities essential for teas intended to age over decades.

From Beverage to Time-Based Asset

These inherent qualities—historical legitimacy, structural advantages, and long-standing market consensus—are what transform aged Pu-erh tea cakes from a consumable product into a verifiable time-based asset.

When further layered with factors such as specific mountain origins, ancient tree material, and spring harvests, Pu-erh tea transcends sensory appreciation alone. It enters a category defined by long-term collectibility and clearly articulated appreciation potential, with its value jointly underwritten by time, quality, and market recognition.

This reality is corroborated by the auction record: to date, every Pu-erh tea that has achieved multi-million-dollar prices at international auctions has been presented in cake form.

The Definitive Vessel of Pu-erh Tea Value

Our emphasis on aged Pu-erh tea cakes does not diminish the quality or cultural importance of other forms. Rather, it acknowledges a historical outcome shaped by centuries of practice and market selection.

The Pu-erh tea cake stands as the definitive physical vessel through which Pu-erh tea transcended its origins as a beverage to become both a cultural icon and a store of value. It is the form in which Yunnan Pu-erh Tea completed its transformation—from daily drink to collectible heritage.